The Precious Hours

Essay by Fiona Robinson PRWA

There are quiet obsessions, undercurrents, that run through the work and practice of printmaker Katherine Jones: line, vulnerability, connections with the written word, time. She is a deeply serious artist, making work in which illusive ideas shimmer on the surface and in the depths of her luminous prints.

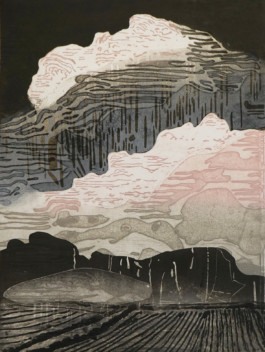

A High Pitch Light, and A High Pitch, ed. 25, collagraph and block print, image: 69 cm x 58.5 cm

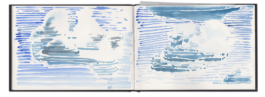

Jones approaches printmaking from the perspective of a painter. Her initial marks are made on card collagraph plates, a process that allows her to retain a greater sense of spontaneity and fluidity than is possible in etching. When she does etch she tends to use a process like sugar-lift that, again, facilitates a free approach. She tackles her subject by making hundreds of pencil drawings in sketchbooks and small watercolours on random scraps of paper. There is always a back-story which is just as thoroughly researched. It is rare for her initial studies to be translated directly into prints. The gathering of visual information allows her to explore a subject in depth and familiarise herself with the possibilities of line, shape, light and colour. Then, when she makes a print, she is so thoroughly versed in her subject that she seamlessly transfers her research onto the collagraph plate. This continuing process of free experimentation gives her the confidence to take risks. She will make fifteen or twenty proofs before she is satisfied that she has solved the visual conundrum and reconciled it with her ideas. She builds up the image on multiple plates and after each printing works back into the print with drawn marks and paint.

Katherine studied printmaking in Cambridge and at Camberwell. She developed her practice through residencies in Germany and the UK and through awards. Following her Masters degree at Camberwell, she received the Julian Trevelyan Memorial Award for printmaking in 2007. Trevelyan’s wife, the painter Mary Fedden, allowed her to use her husband’s studio a couple of days a week for thee or four years. Katherine remembers Fedden, who by that stage was in her nineties, with great fondness and valued her kindness.

Mary Fedden in her garden and The Etching Studio, by her husband Julian Trevelyan

The Precious Hours is the culmination of a year-long residency at Rabley Drawing Centre near Marlborough. Jones has dipped in and out of the location gathering information, absorbing the landscape, the structure of the buildings and the changes in the weather. She has also had access to larger presses than she has at her London studio, which has allowed her to make big work. It has been a hugely fruitful time. She has been enveloped in the beautiful Wiltshire landscape, experienced life on a working farm, and has benefitted enormously from the nurturing atmosphere and support of the Director of Rabley, Meryl Ainslie

One of the strands the exhibition at Rabley addresses is the issue of time. There are oblique references to the writings of Virginia Woolf, an author whose work is hugely significant for Jones. Woolf played with concepts of time in many of her novels – from the truncation of time to one day in Mrs. Dalloway, to the denial of aging in Orlando. Woolf also wrote poignantly about the ageing process in her journals. A journal entry, written in March 1919, when she was 37, contains the following quote:

Life piles up so fast that I have no time to write out the equally fast rising mound of reflections.

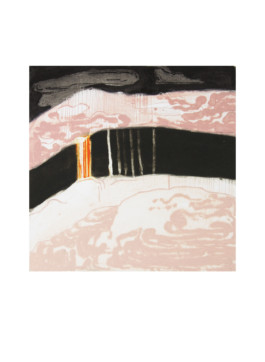

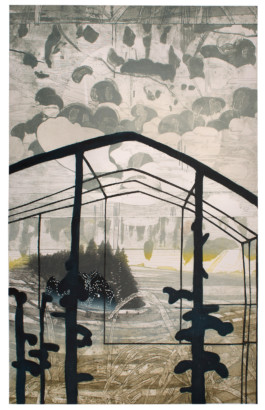

The Precious Hours, ed. 25, collagraph and block print, image: 78.7 cm x 58.5 cm

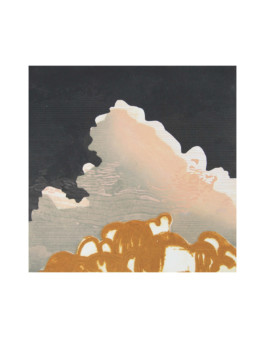

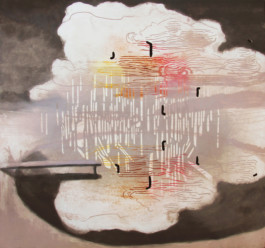

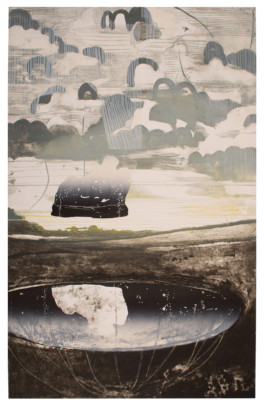

With a young family, time is of the essence for Katherine Jones: lack of time; the passage of time and the terrifying speeding up of time as the world hurtles towards the Armageddon of global warming. This is currently a primary concern in her work and is examined through the evidence of changing cloud behaviours. Cumulus clouds that reflect rather than absorb sunlight are becoming more numerous and consequently more sunlight is reflected back into the atmosphere thus increasing the warming process. Compared to London where Katherine’s studio is based, the skies at Rabley are enormous, the scale is vast. The cloud shapes in her prints originated loosely out of drawings of farm buildings and the curve of the main roof of the house. They began as hatched marks in watercolour on a small scale, moving towards hatched clouds as she sought to capture the patterns. In curves of pinks and greys they pile up, fighting for the space in the lower half of the composition, often sharply outlined against the areas of flat colour above them. She cites the hatched clouds in the background of Canaletto’s beautiful etching, The Portico with the Lantern circa 1740-41 which is in the Royal Collection. Her clouds have become a metaphor for the fragility of life.

Cloud Mass No.2, ed. 25 collagraph and block print, image: 69 cm x 58.5 cm

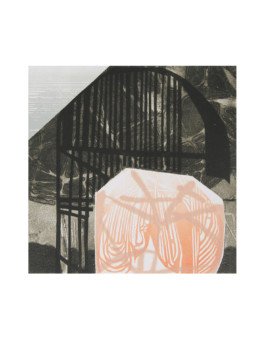

Line in Katherine’s prints is crucial and at Rabley lines proliferate. Verticals pattern the corrugated metal panels that clad the farm buildings, diagonal and curved roofs cut into the skyline and alternating solids and voids appear in the bath-shaped hay pens. Her interest in these structures had its genesis in the work of Joseph Paxton who designed the glasshouses at Chatsworth for the Duke of Devonshire in the early nineteenth century. Paxton experimented with larger and larger structures culminating in the massive achievement of the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition in 1851, a building that was facilitated by the developments in the manufacture of glass and cast iron. It is also relevant to Jones’ work that Paxton started out as a plants man and many of the glasshouses he designed were to accommodate plants imported into England from remote parts of the world, through his agency. The glasshouses were essential for plants from subtropical climates to survive. The collection of plants in the nineteenth century was closely allied to the slave trade. Many of the imported plants became predators in their new environment echoing the predatory nature of the original collectors in countries that were scoured, not just for specimens of plants, but for people to use as slaves.

There are many ironies in the way in which these delicate plants were nurtured, whilst people sold into slavery were not. And this is the nub of what drives Katherine’s work: the importance of protection in all its different forms and the disintegration that occurs when something enters a state of vulnerability.

She sees connections with the use of slave trade routes in the nineteenth century with the 21st century treatment of asylum seekers and immigrants.

THE PRECIOUS HOURS portfolio, ed. 25, image: 27 CM x 27cm, paper: 56 CM x 38 cm, Portfolio folder of seven images. Clockwise: Frame With no Purpose, A Stony Weight of Cloud, Bone and Flint, No Empty Space, Settle In, Calf Hutch

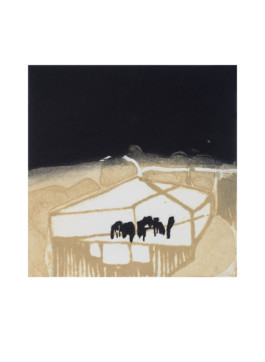

At Rabley her concern with structures as protective environments continued. Early in her residency she became aware of young male calves housed in warm, brightly-lit pens, apparently cocooned in a safe space. In Settle In, their abstracted forms are spotlighted in a glowing white space under a threatening, glowering sky. Ultimately it wasn’t a safe space for these creatures destined for the human table. There was a gap between appearance and truth. In Birds, Layered Song and Aeroplane Noise, she uses a similar hieroglyphic shorthand for rooks skimming the surface of the water and breaking the reflected sky. The seemingly benign clouds innocently scudding the vast skies around Rabley appear as they always have done. But in reality their formation has changed – a change related to global warming and that reveals the fragility of our world.

Birds, Layered Sounds and Aeroplane Noise, ed. 25 collagraph, block print and hand-colour, image: 82 cm x 76.5 cm

There is an interesting analogy with glass as well in Jones’ work. Transparent glass equates with truth, but has the capacity to reflect and reveal. Opaque glass conceals but can also protect. As a barrier, it has the potential to provide safety but to injure when shattered. As a material it offers the same protective qualities that Jones values in enclosed spaces, but it is also fragile. This dichotomy is evident in the spaces between negative and positive shapes throughout her images. In many of her works, including the title piece for the show, The Precious Hours, the linear marks vary in thickness and direction. Straight thread-thin horizontals are balanced with organic sensuous curves and the verticals spill out and tumble down the surface like tears. They have their own life. They replicate solids and voids, but the gaps, sieve-like, allow the protective nature of the enclosed space to ebb away, revealing its vulnerability.

As a mother, Jones is aware that structures have a duality, providing protection but restricting freedom. Many of her early works have elements that refer to domesticity: baths, chairs and references to the safe space inside a house. Her interest in the concept of a safe space has echoes of Gaston Bachelard’s movement in The Poetics of Space, through the domestic spaces of home, a metaphor for the spaces of the interior workings of the mind. The connections are with memory, intimacy and the soul. Jones’ images are the outer manifestation of interiority, of deeply held concerns and convictions. Bachelard’s meanderings through architectural spaces correlate with her absorption of numerous ideas and the positioning of them in her works as possible interpretations, not all of which come to fruition. They are hints, suggestions, alternative route maps to the one she as artist eventually selects. Her concentration on the significance of clouds in The Precious Hours encompasses her other concerns. Clouds are ungraspable, ephemeral. They drift, speed, appear and disappear, they mask the sun or the moon. They are indicators, signifying change. Reflected in water they tempt but evade. Throughout Jones’ work nothing is quite what it seems. Her layering of colour, line, form and motif masks what is underneath the surface. Strata of visual references to landscape ascend reaching upwards for something as unattainable as the clouds reflected in the water of a pond.

Fiona Robinson, 2018

Basin, ed. 25, collagraph and block print, image: 78 cm x 58 cm, paper: 92 cm x 71 cm

An Upside Cup, ed. V/E collagraph and block print, image: 131 cm x 81 cm, paper: 131 cm x 81 cm

Cold Frame, ed. V/E collagraph and block print, image: 131 cm x 81cm. paper: 131 cm x 81 cm

Rabley Pond, Triptych, ed. V/E collagraph and block print, image: 231 cm x 111 cm